I pitched this to a couple of the bigger litblogs out there. They passed on it, and the cycle for both Reynolds’ and Thackray’s books has probably cycled by to the point where the smaller litblogs would probably pass on it as well, so I’m just going to go ahead and post it here before both these books fall into the pulpy schizo-amnesiac lack-of-existence that defines The Recent Past.

Back when they were both writing for UK weekly music paper Melody Maker in the early 1990’s, Everett True was the rockstar critic who everybody talked about and Simon Reynolds was the nerdier less-famous Oxford graduate. 25 years later and if Simon Reynolds isn’t a rockstar, he’s definitely one of the most prominent music critics working today. His books get published by Harper Collins in the US and reviewed in The New York Times. His latest, a history of glam rock called Shock and Awe [1], was recently named an NPR Great Read of 2016.

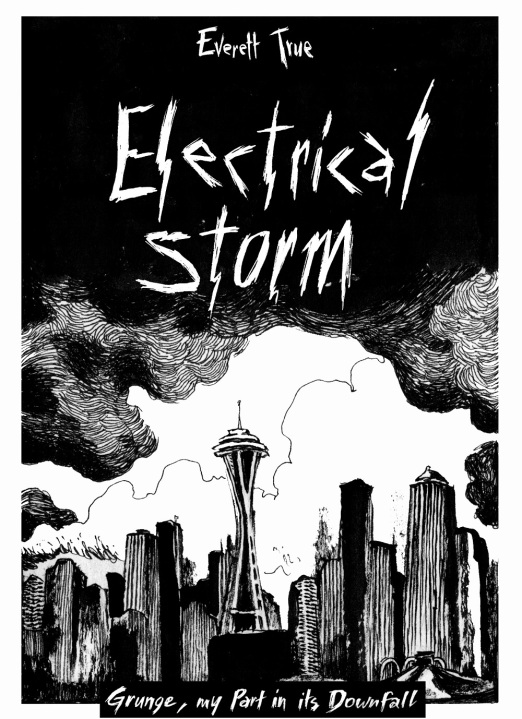

As for Everett True, he barely exists today—an occasional article here, an article there, most of which appear on his personal blog—but if there’s any justice in the world his new memoir, The Electrical Storm, will change all that.

The Electrical Storm, beautifully illustrated by French artist Vincent Vanoli (the drawings are almost as hilarious and revealing as the prose) tells the story of Everett True’s life through a series of flashbacks. In reality, there has never been, in a corporeal sense, an Everett True at all. It’s the nom-de-plume of one Jerry Thackray, who as a young man was so shy and awkward that he invented two alter-egos for himself—Thackray has also recorded and performed as The Legend! (and yes, the exclamation point is part of the name)—and allowed both personas to become more famous, more notorious, than Thackray could ever be.

So as the book unfolds, it feels like a ghost is speaking to you—one out of time, out of thin air, grasping, gasping—and a powerful narrative emerges. The Electrical Storm tells the story of how a loser [2] became a winner, and then how he became a loser again, haunted by the deaths of friends he made along the way.

About those friends. In a Wikipedia sense, Everett True is best-known as the first critic in the UK to write about Nirvana. He became friends with the band (along with, if this book is anything to go on, seemingly every underground band in the US) and introduced Kurt Cobain to Courtney Love. He’s the guy who wheeled Cobain onstage when Nirvana played the Reading Festival in 1992. He recorded the first single released by Creation Records (later to put out records by Oasis, My Bloody Valentine, etc.) And when True’s roommates formed a band called Huggy Bear in the early 90’s, he became one of the earliest UK champions of Riot Grrrl. His enthusiasm and fierce opinions made him a polarizing figure in the 90’s underground, to the point where threats of violence followed him wherever he went. In the early 2000’s, he started a couple of magazines, Careless Talk Costs Lives and Plan B, the former lost half its revenue after True insisted on publishing a negative review of the debut album from buzz band The Vines and the band’s record company/PR agency pulled their advertising in response. [3]

So you know the man has some good stories to tell.

The thing you need to know about Everett True is that on his best day, all egomania & starfucking (both figurative & literal) aside, he was one of the best writers to ever write about music, easily in any Top 15 list you want to make. He could match the gonzo energy and flashes of insight of Lester Bangs, the irreverent deconstructions of Richard Meltzer, the mythmaking poetry of Gina Arnold, the interviewing capability of Paul Morley. And on a Melody Maker staff loaded with talent like Simon Reynolds, Caitlin Moran, Neil Kulkarni, David Stubbs, Taylor Parkes, and so many more—possibly the greatest roster any music publication ever assembled—-his fame at the time eclipsed all the others. He’s the only music critic to act like a rockstar and get away with it. “I was certainly a bigger star than 95 per cent of the musicians I met,” he writes, “and earning more from music, too. More people knew who I was, more copies of my work sold, everything that stardom is measured by…I was more creative as well.”

And even on his worst day, the man could talk some serious trash. No one ever wrote a better evisceration of U2, or of The Cranberries for that matter. After True ripped the band in print, Billy Corgan was inspired to write the Smashing Pumpkins song “Rocket.” True’s response, in the form of a live review, cost Melody Maker a cover story with the band.

Billy Corgan is a media slut, a corporate whore in the lowest, most pitifully sycophantic way. He doesn’t have a trace of originality, of poetry, of soul inside of him. He is all smugness, all knowing steals and money-grabbing finesse. He is an irritation, a minor one, but one which grows with each passing sales figure.

In his heyday, Everett True could turn an unknown band—or in the case of Seattle, an unknown music scene—into a household name. And if he wasn’t always able to destroy a band’s career, he was at least able to get under their skin. Here’s an entry from the book entitled “Eddie.”

The scene is a London hotel bar, and the band are being interviewed by Q Magazine. An hour into the proceedings, singer and lyricist Eddie Vedder is handed a copy of Melody Maker containing a review of their latest show. His eye runs over such remarks as “that sensitive, overblown, preening, gibbering pretence of a poet…suffers from a messiah complex…sings like Phil Collins with a backache…his band are cock-rock strutters extraordinaire…”

Which, regardless of how you feel about Pearl Jam, is more or less true. it’s just that Pearl Jam fans see those qualities as positives while True sees them as negatives. So how does Eddie react to the review?

“This is unbelievable,” Eddie stares into the paper. “Just unbelievable. That guy’s not listening to the music at all…” He continues perusing the review, face turning to thunder while the rest of us make nervous chit-chat. Eddie stands up. “Fuck these fucking people,” he tosses the paper aside with a scowl; then, turning to your innocent Q reporter, he adds with unconcealed loathing, “Fuck you…Fuck ‘em, fuck the whole thing. Because,” his voice rises to an anguished pitch, “it’s totally fucked. Totally ridiculous. That’s why I’m fucking quitting everything. I don’t need to be told anything. I remove myself from the whole situation. It’s unbelievable,” he stalks out of the bar. “Unbelievable.”

But then here’s a story about Jerry Thackray, in a book that’s supposed to be about Everett True. Thackray’s high school band decides to call themselves Blowjob, and he asks his bandmates what the word means. They tell him it’s because he blows into a recorder (yes, Thackray plays recorder in a punk rock band). Enthused about finally being in a band, he writes their name all over his notebook. A teacher sees it and he’s thrown into detention.

It isn’t the last time his naive enthusiasm gets him in trouble. A lot of the stories here involve drinking and various amounts of hedonism, probably because life as a touring musician, to say nothing of a touring music critic, is more boring than anything else. [4] People sit around and talk. They hurt each other emotionally, and sometimes physically. This entry’s from 1993, and gives some hint of the darkness at the heart of The Electrical Storm.

I’m at home. My girlfriend…let’s just say my girlfriend is in hospital.

I’m at home. Nothing feels good anymore.

A couple of weeks earlier I was hospitalized at Reading Festival—checked in to the local infirmary because a couple of doctors wanted to monitor the level of alcohol in my blood. This is a false memory: Reading Festival happens AFTER the events documented here. That’s easily verified. Just count the bodies. In my mind though, everything happens simultaneously. I’m lying on a blank white bed staring at the ceiling wondering where my buddies have gone. Isolated. No one comes to see me so I check myself out in time for night-time drinks back at the Ramada. Someone passes me a water. I drink it straight down. It’s not water. It’s a triple vodka, but I don’t notice. My girlfriend walks out on me again.

Is this the same Reading Festival that I’m sat slumped at the back of the main stage and the crowd stat chanting my name? Within 20 seconds, there are thousands upon thousands of people chanting my name. “Everett True. Everett True.” What do they want from me? “Everett True. Everett True.” Why do they call my name? I cannot mend anything.

I’m at home and my flatmate has disappeared and my girlfriend is…gone. Not that I blame her. No one wants to go near me, touch me. I bring death.

I think I see something in a fireplace. It’s not possible. The fireplace hasn’t been used in years but I think I can see a movement, something fluttering. Fluttering in a fireplace, like that first note that got burnt. It spooks me. The house is empty, deserted. All my friends long since departed. I have an overwhelming desire for human contact, and so I call her. She said I could, any time. Even so, it’s the first time we’ve spoken since…well, you know when.

A strangely stifled voice answers the phone.

“So you heard the news then…?”

Kristen is dead.

There hasn’t been a music critic as successful—success in this case measured by influence and power—since True’s heyday and yet, and yet, most of The Electrical Storm’s stories are about failure. Poet Bill Knott is the only writer I know of to have complained this bitterly, this movingly, about the indignities of self-publishing. Here’s True in the introduction.

Mention grunge, a little voice inside me goes. Mention grunge and sell a million copies. Mention grunge, and folk will queue up once again in their hordes to fawn at your feet. Mention grunge, and the reality of your situation—a self-published biography selling to a couple of hundreds, because no one else will publish it—will disappear magically. Of course it won’t, but that’s OK.

I guess that’s OK.

That’s Jerry Thackray talking there, not Everett True. The speaker throughout the book veers from True to Thackray and back again, shifting between 1st and 3rd person as if Thackray is still struggling to tell the story in his own voice, as if part of him is worried he still needs True. Even the book’s authorship is conflicted. It’s Everett True’s name on the cover, but most of the stories are from Thackray’s POV. The earliest entry is 1977, predating the invention of True, or The Legend! for that matter, by nearly a decade. It gets confusing at times, but it’s always fascinating. And the distance between the life of Everett True and the life of Jerry Thackray drives a lot of the tension in The Electrical Storm.

At one point Thackray addresses this conflict head on.

If people wanted to sleep with [Everett True] for that reason I was more than fine with that because that’s something that I had control over, that I had created for myself. If they wanted to sleep with Jerry Thackray, or if they wanted to sleep with me because they liked my looks, that’s something I didn’t have control over. That’s a little confused…but I used to have issues with that.

I bet he did. In many ways, he still does. Last year, as part of its “you must use real names” policy, Facebook forced him to change his screen name from Everett True to Jerry Thackray.

Back to the story. In 2009 he moves to Brisbane, Australia. While there, he gets involved editing a music site called Collapse Board that’s more influential than it is profitable [5] and earns a PhD in music criticism—literally, he is now Dr. Jerry Thackray. He gradually finds his contrarian opinions less welcome in a field that, as revenue plummets for musicians and critics, now values consensus over confrontation, seriousness over irreverence. In 2015, Thackray leaves Australia and arrives back in England as one more recently graduated academic looking for work.

And yet there’s something beautiful in this transformation. Back in the 1990’s Everett True had everything and Jerry Thackray was a slug. Today Jerry Thackray holds a PhD and has a wife and three beautiful children, while Everett True is a near-forgotten pariah. The Electrical Storm turns out to be the story of a man who unwittingly murders his doppelganger so that he himself might live.

There’s an irony in seeing Thackray’s journey from anti-intellectual college dropout to middle-aged PhD who quotes academics like Norman Denzin in his book’s introduction. Interestingly, Simon Reynolds hasn’t undergone a similar progression—in his case though I guess it would be from academic to animalistic. In fact, for someone who the Times Literary Supplement (UK) called “the foremost popular music critic of his era,” he hasn’t developed much at all.

Which brings us back to Shock and Awe.

The two books are so different that it feels almost unfair to compare them, to say one is “better” than the other, since they aren’t trying to accomplish the same thing—one’s the story of a person, one’s the story of a music genre—yet they provide such a clear contrast between two different approaches to music writing that it’s useful to examine their differences.

If True’s writing style—irreverent, reckless, passionate to a fault, and likely to result in its author’s death at any moment—perfectly reflected the music and musicians he was writing about back in the 90’s, then it makes sense that Reynolds’ style—reasonable, analytical, bloodless—is so popular today. After all, every musical era gets the music criticism it deserves. [6]Reynolds style is the prevailing critical voice of today. Both omniscient and impotent, this kind of critic writes from a position as someone who has head every note of recorded music—this might actually be true in Reynolds’ case, but the tone gets grating real fast with someone who hasn’t—and takes their authority as a given. Here’s an example from the introduction to Shock and Awe.

That said, one larger definitional issue does warrant addressing: what is it that makes the glamorousness of glam different from the standard-issue razzle-dazzle of pop music? After all, varying degrees of elegance, choreographed stagecraft and spectacle are core features of pop in particular and showbiz in general. One crucial distinction is the sheer self-consciousness with which the glam artists embraced aspects like costume, theatrics and the use of props, which often verged on a parody of glamour rather than its straightforward embrace.

In 2016, this is simply what professional music writing looks like. At best, it’s informative. But more often than not, it’s a humorless slog. Simon Reynolds has many gifts as a critic, but he’s not much of an iconoclast, he’s almost never funny, and there’s something glibly shallow at the core of his writing. True’s writing style is soaked in flaws and idiosyncrasies, and he knows it. Reynolds’ writing is, from a journalistic perspective, flawless. But while you can make an argument that Reynolds is the better writer, it’s been said many times that we love people for their flaws. [7]

Back in 2007, when their statuses were more equal, True took a shot at Reynolds’ style in the Village Voice, lashing out at “the preening prats over at Pitchfork, where an entire generation of Simon Reynolds fans have been allowed to grow unchecked.” Five years later, True was less combative, inviting Reynolds to contribute to his PhD thesis on the state of music criticism. In turn, Reynolds wrote about The Electrical Storm on his blog a few months ago. He said nice things, but still took the opportunity to indulge in a sort of backhanded gloating, especially when writing about Thackray’s doctoral thesis, The Slow Death of Everett True: A Metacriticism. “After all these years ET has taken the plunge into academia,” he writes, implying that it’s taken True 30 years to arrive at a place where Reynolds has been all along. But then he tries to pile on, writing “the plethora of first-person pronouns dotting the text breaks with academic norms, to put it mildly.”

This might have been the case when Reynolds went to school, but the paradigm he’s talking about has been shifting for a long time. , particularly in the social sciences, where current academic thinking has evolved to the point where not only is it acceptable to use the first person In academia, in many cases it’s preferred. Most contemporary academics in the field of qualitative research would see Thackray’s “first person pronouns” as being more intellectually rigorous. They would recognize Thackray’s thesis as a work in autoethnography. They’d talk about it using terms like Affect Theory and New Materialism.

Post-positivist science argues that because all observation is potentially fallible, objectivity is a pose, a false one that can never truly exist. [8] And as such, it’s better to foreground the first person so a reader can more clearly see an author’s potential biases.

While Reynolds body of work is littered with references to Marxist and Critical Theory, they’ve always been the most obvious ones—Derrida, Foucault, etc. i.e. the Beatles of Critical Theory. In a 2008 interview, Reynolds even admitted that “when it comes to theory applied to culture, my forte is making a little go a long way.”

So he’s got a lot of nerve getting snotty over Thackray’s academic bona fides.

The funny thing is that a lot of the Crit Theory guys Reynolds likes so much spent most of their philosophical lives trying to dismantle the idea of objectivity. They talked about how it’s a lie that’s used to serve power as it reinforces the status quo. They talked about how grand narratives should always be suspect—because it’s the person who re-edifies the dominant values of society who gets to tell the story. But then the white, male, privileged, straight, non-revolutionary Simon Reynolds assembles grand narratives for a living, so maybe it’s just the old story about paychecks and blindness.

Anyway, the two writers have been rivals for nearly 30 years now, aware of each other’s differences, and to some extent, each other’s strengths. And now they’ve released new books within months of each other, one more or less ubiquitous, one more or less unknown. Make no mistake, Shock and Awe tells a more-or-less comprehensive story of glam rock, filled with juicy anecdotes and thoughtful thoughts. It feels a little unfinished—you keep waiting for a conclusion that never arrives—and were it not for the timely death of David Bowie, the book’s ending would feel even more abrupt. There’s the unforgivable omission of Adrian Street, the flamboyant pro wrestler from Wales whose androgynous style predated glam by several years. But then Simon Reynolds doesn’t strike me as a wrestling fan. Still, the book displays a healthy willingness to expand the genre beyond its early 70’s existence, recognizing the glam-ness in artists that followed such as Lady Gaga and Prince—though Reynolds fails to note that “Cream” is basically a T Rex homage. At the very least, the book functions as an excellent consumer’s guide to glam.

And yet, and yet, when I set down The Electrical Storm to look out the window [9]I find myself sitting there for a while, lost in my thoughts. Everett True’s book haunts me, it provokes me, it forces me to remember the worst parts of myself.

We tend to bury our embarrassments deep in our subconscious. We try to forget our moments of cruelty, of lame impotence. So when someone writes a book this honest, this self-eviscerating, this (for lack of a better word) true, it sends us down the memory hole, it stirs up actual real feelings inside us, in a way that Reynolds’ reminiscences about seeing T Rex on Top of the Pops don’t. Shock and Awe makes me want to run to the internet and listen to some music. The Electrical Storm just makes me want to run.

In the end, the difference comes down to this. Reynolds writes journalism, and True writes literature. [10]Or as a friend of mine put it, “ET’s book could be a movie, Reynolds is an IKEA assembly manual.” And maybe that’s always been the case, the thing about them that hasn’t changed since the early 90’s. Which is fine. The great thing about art is you don’t have to pick sides. But what does it mean when the marketplace has already chosen a side for us?

Because in my lowest, most wounded moments, I’m almost convinced that Everett True, or Jerry Thackray, or whoever, is a flat-out genius, and this might say more about me than it does about him. And in those same moments, I feel like Simon Reynolds is an opportunistic hack, and that says very little about Reynolds and a great deal about me. [11]On most days lately I feel like I’m living on this weird precipice with elation on one side and annihilation on the other. Most days I feel isolated and lost. The Electrical Storm speaks to these parts of me; it makes me feel less alone. And a marketplace, to say nothing of a criticism, that deems Reynolds’ book essential and True’s book superfluous, is one that believes value is something that can only be measured in money.

Shock and Awe is, by any objective measure, a good book. It’s informative and entertaining. It is, to quote NPR, a great read. But The Electrical Storm is special. It’s as wise and moving a meditation on persona and personhood—the story of a man who served as both Dr. Frankenstein and the monster—as I’ve read in a long time. It’s as raw and broken, as filled with errors both narrative and grammatical, as life itself. And it deserves to make Jerry Thackray more famous than his alter-ego ever was.

[1] I kept waiting for Reynolds to explain the parallels between glam rock and the 2003 invasion of Iraq (“‘shock and awe” of course being the military strategy employed by the US), but it never happened. Interestingly, the phrase “shock and awe” has also been used post-war to sell video games, golf equipment, insecticide, bowling balls, shampoo, condoms, heroin, and now, a Simon Reynolds book.

[2] The word “loser” not used semi-ironically like Beck or Sub Pop used it. We’re talking a real loser, a damp, socially inept squid of a person, virginal & spotty & misshaped & shy (or as True describes himself, “fucking loser-idiot social retard”).

[3] At the time, places like NME, Rolling Stone, New York Times, were calling the band the next Nirvana. Don’t worry if you’ve never heard of The Vines—True lost his advertising, but kept his dignity.

[4] Yes, the hour on stage can be exciting, but the other 23hrs is a lot like your last trip to the airport—endless sitting around & waiting combined w/a few hours of travel in a confined space. The food usually isn’t very good either.

[5] This is the part where I tell you I used to write for Collapse Board.

[6] Or maybe every critical era gets the music it deserves? It’s easier to argue that Lester Bangs created punk than to argue that punk created Lester.

[7] Personally, I think we love them for their idiosyncrasies, the things that make them unique, Sometimes that includes their flaws, sometimes it doesn’t.

[8] Donna Haraway’s Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of. Partial Perspective (1988) is a killer read on this subject, esp. for the poetry in her description of objectivity as “a view from nowhere.” Writes Haraway, “I am arguing for the view from a body, always a complex, contradictory, structuring, and structured body, versus the view from above, from nowhere, from simplicity.”

[9] At the moment, I see a couple of parked cars and some trees & houses off in the distance and all of it is beige & unremarkable, as tends to be the case w/most US scenery these days.

[10] In fact, with its multiple perspectives and constantly shifting timeline, The Electrical Storm reminds me of Cortazar’s Hopscotch, only with whiskey instead of mate, and rock instead of jazz.

[11] And most what it says about me isn’t very good.

Pingback: Outtakes from The Electrical Storm – 1. Wire (Willesden Green, London, 1986) | Music That I Like